| The

Way of Life and the Way of Death in the Book of Mormon

Mack C. Sterling Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute, 1997. Pp. 152–204 The views expressed in this article are the views of the author and do not represent the position of the Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. |

|

The Way of Life and the Way of

Death in the Book of Mormon

Introduction The concept of a way leading to spiritual life in opposition to a way leading to spiritual death pervades the Book of Mormon. Near the end of his great discourse on opposition in all things, Lehi declares that "men are free according to the flesh; . . . And they are free to choose liberty and eternal life through the great Mediator of all men or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil" (2 Nephi 2:27). Likewise, Lehi's son Jacob challenges us to "remember that ye are free to act for yourselves—to choose the way of everlasting death or the way of eternal life" (2 Nephi 10:23). Ultimately, all men who hear the word of God will choose one of these two mutually exclusive possibilities, spiritual life or spiritual death. No other option exists. From the Book of Mormon we learn not only about the existence of these two opposing spiritual realities, spiritual life and spiritual death, but we also learn a great deal about the details of each way. We are instructed precisely as to which choices constitute the way of life and which constitute the way of death. We are informed of the consequences of these choices, both in mortality and in the next life. In mortality, initial choices to walk in the way of death are generally reversible. However, for those who hear the word of God, persistence in the way of death throughout mortality has everlasting implications in eternity. Mortality is therefore of transcendent importance. I suggest that the idea of a way of life eternally opposed to a way of death is the fundamental conceptual substrate for the view of reality held by the Book of Mormon prophets. As such, this idea underlies the teachings of the book and overtly constitutes the structural framework of many of its major discourses. To illustrate this thesis, I will examine in detail the following nine texts: Alma 12:31–37; 2 Nephi 9; Mosiah 2–5; Mosiah 15–16; Mosiah 26:20–28; Alma 5; Alma 41:3–8; Moroni 7:5–20; and 1 Nephi 8, 11–15 together with 2 Nephi 31:17–32:5.1 I have chosen these texts because they devote approximately equal weight to describing each of the two ways. I will define what the texts have to say about the ways of life and death during the time of choosing, the probationary period. I will also describe what they say about the eternal consequences of the choices we make during probation, namely, the nature of both spiritual life and spiritual death. I will summarize my conception of the message of each text with a diagram, which will serve to illustrate more graphically the opposition between the way of life and the way of death. The portrayal of the way of death in the Book of Mormon as the exact opposite, inversion, or mirror image of the way of life will become clear. After considering the contributions of each of the texts to our understanding of the way of life versus the way of death, I will summarize the conclusions I have drawn and discuss their implications. Before proceeding, it is necessary to discuss the concept of the probationary period presented in the Book of Mormon. The probationary period was instituted by God in response to the fact that mankind, following our first parents, has voluntarily turned away from God and become carnal, sensual, and devilish (see Mosiah 16:3–4; 3:19; Alma 42:9–12; 2 Nephi 2:26–27). Rather than allowing the full consequences of eternal law to act upon us immediately in this carnal state and causing us to become endlessly lost and forever spiritually dead, God has granted us the probationary time or the day of salvation (see Alma 42:4, 9, 10; 2 Nephi 2:21; Alma 12:24; Jacob 6:5–7; Alma 34:31–32). During probation, or the light of day, God extends mercy to us, giving us an opportunity to repent and turn back to him. This probationary period is a gift to all mankind through the atonement of Christ (see 2 Nephi 2:21, 26–29; Alma 34:9–16, 31–32). However, the probationary time does not last indefinitely; it eventually ends (see 2 Nephi 33:9; 2:30; 9:27). For those who do not repent in mortality, the day of probation is followed by the night of darkness during which no labor (repentance) can be performed, since the arm of mercy is withdrawn (see Alma 34:32–34; 3 Nephi 27:33; Mosiah 16:12; Jacob 6:5–7). The choices we make during probation determine our fate in the eternal world after probation (see Alma 34:32–36; 12:24). Probation is the time to prepare to meet God and to come to understand the mysteries of God. Alma taught:

Spiritual life results from progressively apprehending the mysteries of God during probation. Spiritual death results from progressively hardening one's heart against God until finally one is irrevocably taken captive by the devil, knowing nothing of the mysteries of God. The end of probation is repeatedly correlated in the Book of Mormon with the end of mortality (see 2 Nephi 2:21, 30; Alma 5:15; 12:24; 34:31–34). It is true that a space (time) is described between physical death and the final judgment and resurrection, during which the spirits of men continue to exist (see 2 Nephi 9:11–14; Alma 40:11–14). However, the possibility of repentance during this intermediate state is not suggested. Thus in the Book of Mormon the probationary period is never portrayed as extending beyond mortality into the spirit world. Indeed, Amulek warns us that if we have procrastinated the day of our repentance until the end of mortality, we will have made ourselves irreversibly subjected to the spirit of the devil without power to repent:

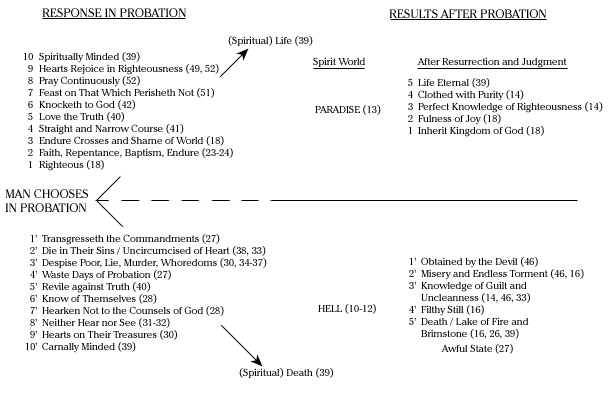

This awful state of captivity to the devil comes only to those who waste the days of their probation after having received the commandments of God (see 2 Nephi 9:27). In contrast, those who die ignorant of the will of God concerning them are described as being covered by Christ's atonement, being delivered from hell, participating in the first resurrection, and receiving eternal life (see 2 Nephi 9:25–26; Mosiah 3:11–12; 15:23–24; Moroni 8:22). In effect, the hearers and readers of the Book of Mormon prophets, both ancient and modern, are told that God will take care of those who pass through mortality without adequate exposure to his commandments. On the other hand, those who hear the word of God in mortality become engaged in the process of choosing between the ways of life and death, with eternal consequences affixed to their choices. When discussing the way of life and the way of death, it is essential to remember the role of Christ. Most of the texts I will examine bear explicit witness of Christ and his atonement while describing life and death. The others presuppose the reality of the atonement. It is imperative to realize that without Christ's atonement there would be no way of life; spiritual death would be the only possibility. Jacob explained that without the atonement "our spirits must become subject to . . . the devil . . . to be shut out from the presence of our God, and to remain with the father of lies, in misery" (2 Nephi 9:8–9). Christ not only brings about the possibility of spiritual life, but he also ensures our opportunity to choose freely between spiritual life and spiritual death during probation: "And the Messiah cometh in the fulness of time, that he may redeem the children of men from the fall. And because that they are redeemed from the fall they have become free forever, knowing good from evil; to act for themselves and not be acted upon, save it be by the punishment of the law at the great and last day" (2 Nephi 2:26). Finally, as alluded to in this quotation and mentioned previously, Christ's atonement brings about the time of probation by holding off the punishment of the law until the great and last day. In summary, Christ brings to pass the choice between life and death by providing the option of spiritual life; he ensures our freedom to choose between the two (agency); and he gives us time to choose (probation). It is possible at this point to present a simple schematic diagram or model of the Nephite prophets" conception of the ideas of the way of life, the way of death, probation, and the state after probation:

Accountable individuals are placed in a state of probation to choose between spiritual life and spiritual death. In the diagram above, the ascending line represents progressive acquisition of spiritual life during probation. The descending line represents a similar descent into spiritual death. The divergence of the two lines represents the separation of mankind into two groups, depending on their response to the word of God (see 1 Nephi 12:18; 14:7; 2 Nephi 30:10). After probation, man receives either eternal spiritual life or eternal spiritual death. This relatively simple conceptual model underlies the Book of Mormon presentation of spiritual reality, as I will now demonstrate in detail. EXPOSITION Alma 12:31–37

Alma 12:31–37 is a concise but thorough summary of the opposing concepts of the ways of life and death (see fig. 1). Man, who has been placed in a state to act, breaks the first commandment, which provokes God (first provocation) and results in the first spiritual death. This triad of initial sin, leading to the provocation of God and the imposition of a penalty by God (first death) can apply to at least three related situations: (1) the transgression of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (see 2 Nephi 2:15–19; Mosiah 16:3; Alma 42:2–7); (2) Israel's inability to keep the law of God in the wilderness (see Jacob 1:7); and, most importantly, (3) the first sin(s) each individual commits after becoming accountable. None of us begins in probation perfectly capable of keeping the law of God. Therefore we all provoke God and consequently suffer the first spiritual death. This comes as a result both of Adam's fall and of our own unrepented, accountable sins. Adam's fall causes us to be removed from the physical presence of God (see Helaman 14:15–17). Our own sins alienate us spiritually from God (see Alma 12:9–11).

Figure 1. Alma 12:31-37 Since we cannot initially keep the law of God (first commandment), God gives us all the second commandment: to repent. The probationary period is the time given to each individual to respond to the second commandment. Man's response to the second commandment determines his eternal fate. He can "harden not" his heart and repent, in which case he receives mercy and a remission of sins, eventually entering the rest of God. The idea of the rest of God is well-developed in the Book of Mormon. It refers to being with or entering the presence of God, whether in mortality (see Moroni 7:3), the spirit world (see Alma 40:12; Moroni 10:34), or after the resurrection (see Alma 13:29; 3 Nephi 27:19). It requires both a remission (forgiveness) of sins (Alma 13:16) and overcoming sin or becoming sanctified (3 Nephi 27:19). Mormon explains that rest in the kingdom of God is given to those who perform the labor of mortality, that of conquering the enemy of all righteousness (see Moroni 9:6). Those who complete this great labor2 of the probationary period, repentance, become pure and rest from their labors with God (see Alma 13:10–12). Thus the idea of the rest of God summarizes all the blessings of choosing righteousness. Contrasted with repentance is the only other option: to harden one's heart and refuse to repent. Those who elect this path break the second commandment and commit the second or last provocation. They have no claim on mercy, and justice mandates the penalty of the second or last death, which is also described as the everlasting death of the soul. More details about the second death will be discussed subsequently. Here, it must be emphasized that this second death comes upon all who hear the word of God but do not repent during the probationary period. It is also apparent that the penalty of the second provocation, the second death, is withheld during the probationary period, coming upon those who fail to repent only after probation ends. 2 Nephi 9 Second Nephi 9 is an extensive and penetrating meditation on the way of life and the way of death by the prophet Jacob. Space does not permit quotation of this entire chapter. In figure 2, I have summarized Jacob's teachings and organized them according to the two types of opposing responses we can make to the will of God during probation and the consequent opposite results after probation. Interspersed through 2 Nephi 9 is a thorough description of the choices in probation that lead to spiritual life on the one hand and to spiritual death on the other. As is readily apparent in figure 2, Jacob describes the two ways in virtually opposite terms. Spiritual life results from initially desiring righteousness, faith, repentance, baptism, and enduring to the end in a quest for truth and holiness from God. Spiritual death results from persisting in sin, refusing to repent, desiring the treasures of the world, and rejecting the search for the truth that comes from God, while trusting in the knowledge of man. Jacob describes clearly the awful state that results from wasting the days of mortal probation. In the spirit world after mortality, the unrighteous—those who have followed the way of death in probation—experience a state of spiritual death and captivity to the devil called hell. The righteous—who have followed the way of life—experience paradise. Alma describes the spirit world in almost the same terms, placing the righteous in paradise, a state of happiness, peace, and rest. The wicked are found in outer darkness, a state of fear of and captivity to the devil (see Alma 40:11–14). Hell and outer darkness are thus equivalent terms, referring to the awful state of the wicked in the spirit world after mortal probation. It is also apparent that the two divisions in the spirit world described by Jacob and Alma are consequent to the two types of response during probation, continual repentance contrasted with wasting of probation by refusing to repent. Consistent with all teaching in the Book of Mormon, Jacob places the final judgment after the resurrection (see 2 Nephi 9:15, 22). After resurrection and judgment, the righteous spirits in paradise inherit the kingdom of God or eternal life, possessing purity and a fulness of joy. The fate of the unrighteous spirits in hell is described in precisely opposite terms. After resurrection they are obtained by the devil, persisting in a state of spiritual death and possessing filthiness and misery. This state is metaphorically described as a lake of fire and brimstone.

Figure 2. 2 Nephi 9 In summary, Jacob teaches us that those who choose good during probation attain paradise in the spirit world and eternal life in the kingdom of God after the resurrection. Those who choose evil attain hell in the spirit world and endless torment as captives of the devil after resurrection. No other options are described. Mosiah 2–5 King Benjamin's powerful sermon and the response of his hearers are related in Mosiah 2–5. Examination of King Benjamin's words and the powerful righteous response of his subjects reveals essentially the same concepts of the way of life and the way of death as presented in Jacob's masterpiece just described. One difference is that no significant information about the spirit world or the resurrection is presented by King Benjamin. Mankind is shown to divide itself into two groups by choices in probation, either growing in spiritual life or persisting in spiritual death. Some information about each group at the final judgment and their opposite fates after the judgment is given (see fig. 3). For the first time in the Book of Mormon, the beginning of one's journey in the way of life is explained as a birth. The subjects of King Benjamin who entered into a covenant with God are described as becoming spiritually begotten or born of Christ (see Mosiah 5:5–7). This spiritual birth involves a mighty change of heart, which disposes one to do good continually (see Mosiah 5:2) and is coincident with a remission of sins (see Mosiah 4:2–3). After this beginning, one's challenge is to retain a remission of sins by remembering God and one's fellow man (see Mosiah 4:11–12, 26) and to be steadfast and immovable in good works until the end of mortality (see Mosiah 5:8, 15). Those who do these things eventually become sealed to God (see Mosiah 5:15). King Benjamin emphasizes that all people in mortality have natural tendencies to choose evil, to follow the way of death (see Mosiah 3:19). As a result, we are all disposed to proceed to some extent down the way of death. In order to turn out of the way of death into the way of life we must undergo the spiritual birth described above. Those who neither repent nor become born of God follow, instead, their natural inclinations to obey the evil spirit. They continue to transgress and bring forth evil works (see Mosiah 2:32, 36–38; 3:25). They die, as they began, as enemies to God (see Mosiah 2:38).

Figure 3. Mosiah 2-5 Judgment occurs at some point after mortal death (see Mosiah 2:33, 38–39; 3:18, 24). Those who have brought forth good works are called by the name of Christ, claimed by mercy, and found on the right hand of God (see Mosiah 5:8–9). They dwell with God in heaven, enjoying everlasting salvation and happiness (see Mosiah 2:41; 5:15). Those on the left hand of God at judgment are exposed to justice after bringing forth evil works during probation and having been called by some name other than that of Christ (see Mosiah 2:38–39; 3:24–27; 5:10). These shrink from the presence of God into a state of damnation and endless torment or lake of fire and brimstone. This is required by justice (see Mosiah 2:33, 38; 3:25–26) and is identical to the second death and hell described by Alma and Jacob. As with the previous texts considered, the details of the way of life are presented as categorical opposites to the details of the way of death. Mosiah 15–16 In his marvelous and provocative address to King Noah, Abinadi proclaims Christ as the forthcoming savior of the world and as the fulfillment of the law of Moses. He then describes two types of response to Christ during probation and the consequences of each type of response after probation. The two sets of responses and consequences are described as mirror images, one leading eventually to eternal life and the other to endless damnation (see fig. 4). Abinadi declares that all mankind is participating in a fallen state (see Mosiah 16:3–4). For those to whom knowledge of God is given, the arm of God's mercy is extended (see Mosiah 15:26; 16:12). The reception of mercy and spiritual life is dependent on the response of each individual. Abinadi differentiates the response which leads to life from that which leads to death in terms of one's response to the voice or words of God or his prophets. Those who receive the words of the prophets are led to believe, repent, and keep the commandments. They bring forth good works, are redeemed by mercy, and come forth in the first resurrection (resurrection of endless life) to dwell with God in eternal life. They are characterized as the seed of Christ, consistent with King Benjamin's declaration that those who are spiritually begotten or born of God are the sons and daughters of Christ (see Mosiah 5:5–7). The hallmark of the way of death is to refuse to hearken to the voice of the Lord. This response is characterized by following one's own (carnal) desires, rebelling against God, and persisting in the carnal nature. Evil works are brought forth. Redemption is not possible, being inconsistent with the nature of God (see Mosiah 15:27), and the unrepentant are claimed by justice. These people come forth after the first resurrection in the resurrection of endless damnation and are delivered to the devil. Their own choices—refusal to hearken to the voice of God—have placed them in the power of the devil.

Figure 4. Mosiah 5-16 Final judgment occurs after the resurrection (see Mosiah 16:10–11). However, it is implicit in Abinadi's teaching that there must be some judgment prior to the resurrection. This is apparent from Abinadi's description of two temporally separated resurrections. Obviously, at the time of the first resurrection there must be a separation of mankind into two groups: those who are able to participate in the first resurrection and those who are not. This must, of necessity, occur before resurrection and final judgment. The division of the inhabitants of the spirit world into paradise and hell or outer darkness, described previously, also supports the concept of some judgment prior to resurrection and final judgment. Mosiah 26:20–28 Abinadi's discourse, just discussed, proclaims the essential equivalence of the words of the holy prophets and the words or voice of the Lord (see Mosiah 15:11, 22; 16:2). Extrapolating from this, one would expect God himself to communicate information about the plan of salvation in terms of the two mutually exclusive categories of life and death, as his prophets did in the Book of Mormon. This extrapolation is confirmed by experiences in the life of Alma1. Alma was converted by the words of the prophet Abinadi (see Mosiah 17:2), which I have summarized in the preceding section. Abinadi obviously structured his discourse by opposing the concepts of the way of life and the way of death. Near the end of his life Alma was given a promise of eternal life by the Lord. Here, the voice of the Lord outlines the way of salvation and the way of death in terms essentially identical to those of the prophet Abinadi:

* Terms implied but not overtly given in the text This text yields itself easily to a diagram (see fig. 5). Here the Lord differentiates the response which leads to life from that which leads to death in terms of man's willingness to hear his voice. Those who seek righteousness in this fashion come forth on the right hand of God; resurrection at the first trump is implied but not overtly stated. Those who refuse redemption by refusing to hear the voice of the Lord come forth at the second trump. Their place on the left hand of God is implied, but not expressed. King Benjamin similarly placed the righteous on the right hand of God and the wicked on the left at judgment. Alma 5 Alma2 was obviously heavily influenced by King Benjamin, Abinadi, and his own father in his conception of the gospel. Alma2's great speech to the church at Zarahemla (see Alma 5) draws sharp contrasts between the way of life and the way of death, echoing and amplifying many of the teachings of his predecessors (see fig. 6). In this discourse, Alma contrasts the redeemed state of those converted by his father with their condition before their conversion to Christ, when they were in a deep sleep, in darkness, encircled by the chains of hell, and awaiting an everlasting destruction. This, of course, is a powerful description of the spiritual alienation of the first spiritual death, which all accountable souls experience to a greater or lesser degree. The reversibility of this first spiritual death during probation by being born of God is confirmed by Alma's description of the mighty change of heart his father's converts experienced. By being born of God they were brought into the light, having awakened to God. Thus the chains of hell binding them were loosed and they were delivered from the hell or everlasting destruction that had formerly awaited them (see Alma 5:6–9). The spiritual life that begins with being born of God must be sustained, or it can be lost. This possibility of loss is implicit in Alma's question: "If ye have experienced a change of heart and ye have felt to sing the song of redeeming love, I would ask, can ye feel so now?" (Alma 5:26). Those who are born of God must continually strive to develop humility and walk blameless before God. As they do this, they are sanctified by the Holy Spirit and bring forth good works, retaining God's image in their countenances; their garments are eventually washed white. They ultimately receive an inheritance in the kingdom of God (see Alma 5:13, 27, 28, 54). On the other hand, those who do not turn to God from their state of darkness and sleep bring forth evil works, progressively subjecting themselves to the devil, and their garments remain stained. At judgment, those with stained garments are hewn down and cast out into the unquenchable fire as children of the devil's kingdom. Thus they experience the everlasting destruction, or second death, which awaits all those who persist in the state of darkness (first death), by choosing not to repent (see Alma 5:18–25, 41–42, 52).

Figure 6. Alma 5 Alma, like Abinadi, teaches that the essential feature of the way of life is to "hearken to the voice of the good shepherd" (Alma 5:37–39). Alma also insists that those who do not follow the voice of the good shepherd follow the voice of the devil. The fold of Christ, the good shepherd, consists of those who are following his voice, which leads them to life. Thus membership in the fold of the good shepherd is not necessarily equivalent to nominal membership in the church. The fold of the devil consists of those who are following the voice of the devil, which leads to everlasting destruction or death. All those who do not belong to the fold of Christ belong to the fold of the devil (see Alma 5:37–39). A critical insight into the source of good works is provided by Alma's comment that "whatsoever is good cometh from God, and whatsoever is evil cometh from the devil" (Alma 5:40). Man can only obtain goodness from God by hearkening to the voice of God. Therefore, good works are produced by an interaction of our efforts with God's grace. On his own, man cannot bring forth the works of righteousness, the good fruit we must produce to avoid being hewn down and cast into the fire (see Alma 5:33–35). A mighty change of heart must be wrought by the power of God, which empowers men to work righteousness. Thus the very existence of the way of life is a gift of God, and likewise the power to proceed in the way of life. The first gift is given to all men, the second only to those who strive to hear and heed the voice of God (see Alma 5:33–41, 57). Alma 41:3–8 Late in life Alma2 gave a charge to each of his three sons concerning the things of righteousness. Part of his teaching to Corianton contains a rather detailed exposition of the plan of restoration, which is presented as a strict dichotomy between the results of choosing the way of life and those of choosing the way of death:

Alma describes man as choosing according to his desires to do either good or evil (see fig. 7). Those who repent and desire righteousness until the end of their days have good restored to them at the last day (final judgment). This restoration of good is the natural and unavoidable consequence (because of Christ's atonement, which prepares the way of life) of their choices, which bring them to happiness in the kingdom of God. On the other hand, those who desire evil all the day long (during the time of probation) have evil restored to them when the night (the end of probation) comes. The evil restored to them is endless misery, the unavoidable consequence of remaining in a state of sin contrary to the nature of happiness (see Alma 41:11).

Figure 7. Alma 41:3-8 Alma articulates clearly the concept that what men eventually become—either happy in the kingdom of God or miserable in the kingdom of the devil—is determined by the choices they make. The ultimate consequences of these choices (restoration) are fixed according to the unalterable decrees of God, which must be in harmony with his just nature (see Alma 41:2). Thus, seen from one perspective, men "are their own judges" (Alma 41:7) since their own choices determine their final outcome. Seen from another perspective, God judges, since the natural and unavoidable consequences of men's choices are fixed by God's word (decree) or justice. It is instructive to note Alma's observation that the option of endless happiness in the kingdom of God is available to all because of the preparations of God (see Alma 41:8). Without these preparations, the only possibility would be to remain in the natural and carnal state and to reap the bitterness and misery of the way of death (see Alma 41:11–13). Moroni 7:5–20

Moroni 7 contains Mormon's teachings on faith, hope, and charity. Verses 5–20, quoted above, constitute an introduction to more specific teachings on faith, hope, and charity. Similar to the texts examined previously, opposing terms or concepts are used to portray the two options available to all men. Mormon begins by considering good works, the fruit we must produce in order to inherit the kingdom of God. He proclaims that the production of truly good works necessarily implies that the person is good, since an evil person cannot bring forth good works. Good works or good gifts are those produced as a result of proper motivation or "real intent." This idea serves as the background to Mormon's subsequent teaching that charity is the ultimate motivation for all good (see Moroni 7:44–48). Mormon maintains that a good man must be a servant and follower of Christ, since all good comes from God. In other words, God is the source of man's ability to be or become good. Mormon implies that those who do not follow Christ are followers of the devil and capable only of evil gifts or works. This is, of course, precisely the same concept King Benjamin and Abinadi taught about the natural or fallen man: he is, because of his carnal nature, an enemy to God; in order to become righteous, he must turn to God through the power of the atonement (see Mosiah 3:19; 16:3–5). The two fountains mentioned in verse 11 can be interpreted in two ways. The good and bitter fountains can represent Christ and the devil respectively. This would be consistent with other representations of Christ as the fountain of living water or righteousness (see 1 Nephi 11:25; Jeremiah 2:13; Ether 12:28) and the devil as the fountain of filthy water (see 1 Nephi 12:16; 15:26–29, 34–35). Picturing Christ as the good fountain and the devil as the bitter fountain parallels the concept expressed in verse 12 that "all things which are good cometh of God; and that which is evil cometh of the devil." Alternatively, the good and bitter fountains can represent good and evil persons respectively. Good works flow from the good person, a servant of Christ. Evil works flow from an evil person, a servant of the devil. Both interpretations are compatible: we become secondary fountains, our natures dependent on the primary fountain from which we are drinking. One acquires spiritual life by drinking from the good fountain, progressively acquiring the nature of Christ; one attains spiritual death by persisting in drinking from the bitter fountain, progressively acquiring the nature of the devil. Mormon emphasizes, as does Alma (see Alma 41:7), the responsibility of mankind to judge between good and evil. We are continuously beset with choices of good and evil. God has given us the spirit or light of Christ to enable us to judge with discernment. That which comes from God (the source of all good) invites and entices one to do good and love God. Therefore, as we receive the things of God, we are enticed to turn more fully to God and receive even more from him, which leads to an even greater desire for goodness in an ever-increasing crescendo until one is completely good. A practical definition of a good man, then, is one who is turned toward God and is in the process of making choices that move him closer to God. The evil man, on the other hand, is not turned toward God and is, therefore, faced toward the devil. He is making choices that move him ever closer to the devil. As he receives evil, he is enticed to do and receive even more evil, which results in a continuous downward spiral toward the devil and spiritual death. We have learned from the previous texts that this spiral can be broken only by availing oneself of the power of the atonement through repentance while the arm of mercy is extended. Once the night of darkness or end of probation comes, no such labor can be performed (see Mosiah 3:19; 16:12; Alma 34:32–35; 3 Nephi 27:33). It is worthwhile to reflect briefly on what is meant by good and evil works. I would suggest that good works can be divided into two types: genuine repentance (see Alma 34:32–34) and charitable service or gifts to God and fellow man (see Mosiah 2:17; Moroni 7:48). Evil works consist of everything else. This idea of evil works embraces a great deal, going beyond those acts commonly considered crimes and even beyond those things considered minor sins to include all deeds done without pure intent or not motivated by charity (see Moroni 7:6–8). Evil works are everything less than those we must produce if we are to be pure even as God is pure. It should be apparent from the preceding discussion that Mormon considers the ability to bring forth good works dependent on help from God. In addition Mormon implies that this ability is procured gradually as we "search diligently in the light of Christ" until we "lay hold upon every good thing" (Moroni 7:19). Therefore, we should not despair because of our initial inability to bring forth works motivated purely by charity. Rather, we should continue striving in the light of Christ until we are filled with charity. The complexities of this text make it somewhat more difficult to summarize in a diagram than the preceding ones. An attempt is presented in figure 8.

Figure 8. Moroni 7:5-20 1 Nephi 8, 11–15; 2 Nephi 31:17–32:5 Lehi's dream and Nephi's related visions and commentary contain a vast panorama of symbols, prophecy, and insight that have great relevance to virtually every subsequent event and teaching in the Book of Mormon. Their relevance to our own time is no less. Embedded within these revelations are clearly presented concepts of the opposing ways of life and death. Consider the following:

Thus God, by his work, causes men to choose either peace and eternal life (spiritual life) or destruction and captivity to the devil (spiritual death). In many of the texts discussed previously, the contrasting ways of life and death have been described in virtually opposite terms and phrases. This literary feature is less obvious here. Nonetheless, the great opposition between the two options available for all men is readily apparent (see fig. 9). In the dream, Lehi first finds himself in a dark and dreary wilderness (see 1 Nephi 8:4–7). This suggests the state of fallen man in ignorance, cut off from the presence of God, without knowledge of the way of life (or death). After praying for mercy, Lehi sees a large and spacious field wherein the ways of life and death are symbolically portrayed, as well as the responses of people to these two options. The very manifestation of the way of life, then, is a function of the mercy or grace of God. The way of life is represented as a strait and narrow path, with a rod of iron alongside, leading to the tree of life (see 1 Nephi 8:19–20; 15:21–22). In subsequent commentary on these images (see 2 Nephi 31:17–20), Nephi teaches that in order to gain access to the strait and narrow path, one must enter through a gate representing repentance, baptism, and the initial reception of the Holy Ghost or baptism of fire, which brings a remission of sins. Faith, which is a prerequisite to repentance, is not specifically mentioned in 2 Nephi 31:17 as part of the gate. However, it is implied; furthermore, statements in subsequent verses about the path make it clear that Nephi conceived of faith as integral to the gate (see 2 Nephi 31:18–20). To pass through the gate is essentially equivalent to the idea of being born of God described by King Benjamin and Alma (see Mosiah 5:2–7; Alma 5:6–14). Passing through the gate or being born of God refers to the culminating event in one's initial reception of Christ, the reception of the Holy Ghost, which creates spiritual life within the individual and brings a remission of sins. In the dream, it is difficult to maintain one's way on the path once entered. Many "who had commenced in the path did lose their way, that they wandered off and were lost" (1 Nephi 8:23). The key to staying on the path is clinging to the rod of iron, which represents the word of God (see 1 Nephi 8:30; 15:23–24). Nephi reminds us that we enter the path with unshaken faith in Christ (see 2 Nephi 31:19) and then challenges us as follows:

Staying on the path, then, means to endure to the end in feasting on the words of Christ, while becoming filled with hope and love. The ability to feast on or receive the words of Christ is a gift of the Holy Ghost:

After being initially baptized by fire, we must continue to receive and heed the Holy Ghost until we reach the end of the path. Nephi places eternal life at the end of the strait and narrow path (see 2 Nephi 31:20). Eternal life in Nephi's commentary thus corresponds to the tree of life in Lehi's dream. The tree represents eternal life, the love of God (see 1 Nephi 11:21–22), and Christ himself (see 1 Nephi 11:9–21). Those who persist in the path until the end become filled with love, reenter the presence of Christ, and receive eternal life. These blessings at the end of the path correlate well with the concept of entering the rest of God discussed previously. At the end of the path, Nephi also saw the fountain of living waters, in addition to the tree of life (see 1 Nephi 11:25). Like the tree of life, the fountain represents the love of God, Christ himself, or eternal life. The way of spiritual death is also powerfully portrayed in the dream. Lehi describes five groups of people who walk in the way of death: (1) those who start in the path and become lost because of the mists of darkness (see 1 Nephi 8:22–23); (2) those who taste the fruit, become ashamed, and are lost in forbidden paths (see 1 Nephi 8:28); (3) those who are drowned in the depths of the fountain of filthy water (see 1 Nephi 8:32; 1 Nephi 15:26–27); (4) those who become lost wandering in strange roads (see 1 Nephi 8:32); and (5) those who enter the great and spacious building, which represents the pride of the world and is to be destroyed in a great fall (see 1 Nephi 8:33; 11:34–36). Thus all these people are described as either lost, drowned in the filthy fountain, or destroyed—all metaphorical descriptions of spiritual death. In Nephi's vision, this is summarized by the angel who says, "the mists of darkness are the temptations of the devil, which blindeth the eyes and hardeneth the hearts of the children of men and leadeth them away into broad roads that they perish and are lost" (1 Nephi 12:17). "Broad roads" is an apt metaphor for the way of death in contrast to the strait and narrow path leading to life.

Figure 9. The final fate of those who persist in the broad road(s) leading to death by yielding to temptation and hardening their hearts is vividly described by Nephi:

Those who persist in wickedness until the end of probation are cast off into hell, a place of filthiness, forever separated from God or the tree of life. In the dream, hell is symbolized by the fountain of filthy water and the river that emanates from it (see 1 Nephi 12:16; 15:27–29). Hell is also portrayed as an awful gulf, undoubtedly filled with the filthy water from the fountain, that separates the wicked from the tree of life (see 1 Nephi 15:28) and as a great pit filled by the devil and his children (see 1 Nephi 14:3). Those in hell are captives of the devil (see 1 Nephi 14:4). Nephi describes the division of mankind into two churches: the church of the Lamb of God, composed of the saints of God, and the great and abominable church of the devil, composed of everyone else (see 1 Nephi 14:10–12). The church of the devil is an enemy to the church of the Lamb (see 1 Nephi 13:4–9, 26–28; 14:3, 12–14). Its members are undoubtedly the natural men described by King Benjamin as enemies to God and, by extension, to the church of the Lamb. The church of Christ and the church of the devil described by Nephi correspond respectively to Alma's fold of the good shepherd and fold of the devil (see Alma 5:37–39). It follows that the church of Christ consists of those who hearken to the voice of Christ and the church of the devil consists of the natural men who hearken to the voice of the devil. Summary of Theological Exposition As a result of the fall of Adam, man arrives on earth cut off from the tangible and visible presence of God.3 Additionally, as a result of the fall, man is disposed (not forced) to make choices contrary to the will of God, evil choices. All men, to some extent, make choices according to these natural, carnal desires and therefore alienate themselves spiritually from God. Thus all men participate with their first parents in breaking the first commandment or committing the first provocation of God. They have received as a consequence, the first (spiritual) death. This consists of (1) separation from the physical presence of God caused by Adam's transgression and (2) spiritual separation from the presence of God and Christ caused by our own sins. All men in mortality possess a disposition to do evil. They are therefore natural men, enemies of God, because they are unable to do his will. Following their own natural desires, they inevitably act in opposition to the purposes of God. All men have therefore begun in the way of death, from which there would be no possibility of escape without the atonement of Jesus Christ. The reality of Christ's atonement gives all men the option of turning from the way of death into the way of life. The time given to man to avail himself of the way of life is the probationary period. Since all men have broken the first commandment, they are placed in this probationary state of mortality and given the second commandment: to repent. During probation, man experiences the first spiritual death as a result of his sins and Adam's fall. The full demands of eternal law and justice on his sins, however, are withheld until after probation. The choices man makes in probation determine his eternal fate, either spiritual life or spiritual death. All men who have been given the second commandment to repent, by either the voice of God or his prophets, stand at a crossroads. Christ also stands at this crossroads with us, having brought about the way of life and offering us the knowledge and power to progress in it. Our response to Christ determines which road we take, life or death. A great division in mankind progressively occurs. Probation is the time given us to respond and is therefore the time when the division of mankind into two groups is actually worked out. The end of probation marks a great division between the time of responding and the time of eternal restoration. Way of Life The initial response that leads out of the way of death is to make the effort to consider the words of God, to hear the voice of God. As this is done, knowledge about God is obtained and faith in God arises. The comprehension of God's greatness and goodness results in both sorrow regarding one's previous rebellion against God and a powerful desire to change for the better. Repentance ensues. One becomes willing to enter a covenant with God (baptism). At the appropriate time, the individual receives the baptism of fire by the Holy Ghost. Two critical things follow from this: remission of sins and a mighty change of heart so that the natural disposition to do evil is changed to a disposition to do good. At this juncture, the dominant, although not necessarily the only, desire is to do good. The person has gone through the gate and has begun on the path to eternal life. He is born of God, becoming a child of Christ spiritually. Spiritual life has begun in him. The challenge then is to encourage spiritual growth and maturation, allowing one to become a "man" in Christ. The remission of sins granted when one is born of God is provisional or conditional and must be retained by continual remembrance of God and one's fellow man. As the remission of sins is retained, one walks blameless before God. The individual is legally guiltless, declared legally righteous by the merits of Christ. He is therefore justified, although provisionally. Unconditional or unprovisional justification comes later and involves being unconditionally accepted by God for eternal life and being sealed to God. As one walks in the strait and narrow path that leads to eternal life, retaining a remission of sins, one must continue with faith. He will be nourished by the living water, hearkening to the voice of God and feasting upon the words of Christ, which are received by the Holy Ghost. Progressive reception of the Holy Ghost results in: (1) progressive overcoming of character weaknesses, which have caused sins, until one becomes perfected; (2) progressive knowledge of the mysteries of God until one knows them in full; and (3) progressive acquisition of charity or love until one is filled. Thus those in the way of life become progressively sanctified by the Holy Ghost. As a result of their efforts, combined with the gifts of the spirit (grace of God), they become able to bring forth purely good works. They possess righteousness and are qualified to enter the kingdom of God. They eventually become sealed to God and enter his rest. As noted above, the first spiritual death—the spiritual death of probation—consists of two components: physical separation from the presence of God caused by the fall of Adam and spiritual alienation from God caused by our individual sins. Both components of the first spiritual death are ultimately overcome by walking in the way of life. Our spiritual alienation is overcome by becoming spiritually begotten of God and thereafter growing up in the spirit. Spiritual alienation diminishes proportionately as spiritual life matures in us. Physical separation from the presence of God, although transiently overcome at the judgment for all men (see Helaman 14:15–17), is overcome in a more meaningful and lasting way by those who persist in the way of life. These eventually enter the rest or presence of God, completing the reversal of the first spiritual death. Those who remain in the path until the end of the day of probation enter paradise in the spirit world, a state of peace, rest, and happiness. Having chosen good and brought forth good works, good is restored to them. They come forth in the first resurrection, are found at the right hand of God at judgment, and enter the kingdom of God. Here they dwell with God in eternal life, possessing a fulness of joy and eternal righteousness. They have life. They are the children of God. Way of Death One continues in the way of death by persistently following the carnal desires to which the natural man is disposed. Simultaneously, the heart is hardened and the voice of God is ignored. The things of God are not desired. The spiritual eyes remain blind and the ears deaf. Pride and a sense of self-sufficiency increase. As the will of the devil is followed, the individual is enticed to continue to follow the voice of the devil and remain in a state of rebellion against God. He continues to yield to temptation. He knows progressively less and less of the mysteries of God, descending into spiritual darkness, deeper and deeper into the first spiritual death. He can produce only evil works (works not caused by pure intent or charity) because he does not receive help from the source of all good, Jesus Christ. The arm of mercy, the call to repentance, which is stretched out all the day long, is ignored. Evil is desired all the day long. The days of probation are wasted. The individual becomes progressively bound by the chains of hell until the chains become unbreakable and he is taken captive by the devil. The night of darkness wherein no labor can be performed has arrived. Repentance is no longer possible since probation is over. The second provocation, refusal to keep the second commandment to repent, has been committed. The individual is trapped in wickedness and stained by sin, being filthy, having progressively chosen spiritual death. Those who have yielded themselves to become captives of the devil by refusing to repent during probation suffer the full consequences of their choice of the way of death only after probation. In the spirit world they are cast into outer darkness as possessions of the devil in hell, a state of awful fear. Having chosen evil, evil is restored to them. They come forth in the second resurrection, are found at the left hand of God at the final judgment, and are again cast out into the kingdom of the devil. Here they suffer misery and endless torment, being filthy in a place of filthiness, namely hell, the pit or awful gulf. Their suffering is metaphorically described as being in a lake of fire and brimstone. This is the second death, the absolute spiritual death after probation. The second death is the penalty for the second provocation. Therefore, those who do not accept the atonement to escape the first spiritual death in probation die the second death after probation. They have eternal spiritual death. They are the children of the devil. Only Two Final States for the Souls of Men It should be readily apparent from the preceding presentation that the Book of Mormon describes only two possibilities for all mankind after probation: eternal life or everlasting death. All the righteous, those who hearken to the voice of God and keep his commandments, inherit eternal life, thus entering the rest of God, living in his presence, and possessing joy and purity. In addition, those who die in ignorance without having salvation declared to them are described as being redeemed by the atonement of Christ and inheriting this condition of eternal life. All the wicked receive everlasting spiritual death (hell or second death) after probation. This state is described as a state of misery, torment, fear, filthiness, and captivity to the devil. The wicked are simply those who have salvation declared to them but refuse to hearken to the voice of God and repent. Consider the following from King Benjamin's address:

Alma similarly reminds us that those who persist in rejecting the voice of the good shepherd are following the voice of the devil and become his children (see Alma 5:38–41). It is essential to grasp precisely whom the Book of Mormon is describing as sons (and daughters) of the devil and recipients of endless torment and the second death. This state comes upon all who do not receive forgiveness for their sins. The Book of Mormon prophets do refer to a concept of unpardonable sin, that of denying the Holy Ghost when "it once has had place" in us (Alma 39:6; see Jacob 7:19). Those who commit this unpardonable sin are doomed to the second death or everlasting destruction, having lost all possibility of repentance, forgiveness, and mercy. However, those who commit lesser sins, which can be forgiven, nonetheless ultimately suffer the same fate as those who commit the unpardonable sin, if they refuse to repent during their day of probation. This idea is clearly expressed by Samuel the Lamanite:

Thus those who have the option to repent, but who do not, suffer the never-ending torment of the second death (hell). To assume that only those who commit the unpardonable sin of denying the Holy Ghost suffer the awful state of the second death is to ignore the repeated warnings of the Book of Mormon prophets to those for whom repentance is an option but who choose to remain in their sins (see 1 Nephi 15:27–30, 32–36; 2 Nephi 2:27–29; 9:45–47; Jacob 6:4–11; Mosiah 2:36–40; 16:5, 11–12; 26:25–27; Alma 5:41–42; 12:31–37; 34:33–35). The great division in mankind described by the Book of Mormon is between those who hearken to the voice of God and those who do not, not between those who commit the unpardonable sin and everyone else. DISCUSSION The Way of Life and the Way of Death as Modified Dualism In the Book of Mormon the moral universe of mankind is conceived and portrayed in terms of two great bifurcating paths, the way of life and the way of death, leading respectively to spiritual life and spiritual death. This portrayal of the progressive acquisition of spiritual life as the mirror image opposite of the progressive acquisition of spiritual death reflects a beautiful conceptual symmetry, best illustrated by the diagrams presented previously. In constructing the diagrams, I have taken ideas out of their literary sequence and reordered them into a conceptual framework, which I believe underlies the texts. This conceptual pattern serves as a means of organizing thinking about spiritual life and death. I suggest that this way of thinking about spiritual reality was communicated by God to the minds of his prophets.4 Lehi's dream, the first recorded revelation of this kind in the Book of Mormon, is an especially compelling example.5 Readers more familiar with theological and philosophical terms will recognize the conceptual framework I have described to be simply a modified dualism. Dualism is "a pattern of thought, an antithesis, which is bifurcated into two mutually exclusive categories (e.g. two spirits or two worlds), each of which is qualified by a set of properties and ethical characteristics which are contrary to those under the other antithetic category (e.g. light and good versus darkness and evil)."6 Absolute dualism requires the two opposing persons, ideas, or forces to be equal in power, and eternal, whereas modified dualism does not. The Book of Mormon obviously manifests marked modified dualism.7 Ethical dualism (good vs. evil), soteriological dualism (way of life vs. way of death), cosmic and metaphysical dualism (God vs. the devil), and anthropological dualism (righteous children of Christ vs. wicked natural men) are all very evident, as I have demonstrated in this paper. As mentioned previously, I am convinced that this dualistic conception of reality originated in revelation from God. The Dead Sea Scrolls (especially the Rule of the Community, 1QS) and the Johannine writings (Gospel and Epistles of John, Revelation) are similar to the Book of Mormon in exhibiting marked dualism.8 Some authors have suggested that the author of the Gospel of John may have inherited a dualistic mentality, at least in part, from the community that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls.9 It is not impossible that John's thinking was influenced in this fashion by his cultural milieu. However, it is possible, using the Book of Mormon, to suggest a much more fundamental source for the dualistic character of the Gospel of John. We learn from Nephi (see 1 Nephi 14:18–27) that John was subsequently to have the same or similar visions as Nephi and his father had received. These visions, recorded in 1 Nephi 8, 11–14, are very dualistic, as I have demonstrated. It is probable that God communicated a dualistic perception of reality to John as he had to Lehi and Nephi. This dualism was subsequently reflected in all his writings, including his gospel.10 Life Contrasted with Death Underlies the Entire Book of Mormon In the "Exposition" section of this paper, I purposefully chose texts which treated the issues of spiritual life and death in approximately equal balance, texts which most clearly reflect the modified dualism discussed above.11 In much of the Book of Mormon modified dualism is less overt. Nonetheless, virtually all writings in the Book of Mormon are grounded in the concept of the opposition of the ways of life and death. Some texts concentrate primarily on spiritual life; for example, Alma 32 describes spiritual life metaphorically as a tree growing up from a seed. Other texts concentrate primarily on warning of the risks and nature of spiritual death; for example, Alma discusses such things with his wayward son Corianton (see Alma 39–42). In both these examples, however, descriptions of the opposing alternative are given. Thus in Alma 32 the dangers of casting out or failing to nourish the good seed of God are clearly presented (see Alma 32:38–39). Similarly, while emphasizing to Corianton the eternal destruction that comes on those who persist in sin, Alma also teaches him about the possibility of repentance and the happiness that flows therefrom (see Alma 39:9; 42:29–30). The teachings of Christ to the Nephites after his resurrection recorded in 3 Nephi 12–27 can also be readily separated into opposing descriptions of the way of life and the way of death, although with more emphasis on the way of life. It is instructive to consider two texts, one from Christ's first recorded discourse and one from his last:

I find it remarkable that Christ twice used essentially the same symbols to describe the ways of life and death as were used by Lehi and Nephi. In these statements Jesus clearly confirms the mutually exclusive natures of the paths to life and death. The second text quoted above is the very conclusion to his last recorded public discourse to the Nephites. This constitutes powerful evidence for the critical importance of conceiving spiritual reality in terms of two great bifurcating ways of life and death. Although the focus of this paper has been on spiritual life and death, Book of Mormon teachings about temporal prosperity and temporal destruction can also be readily understood in terms of a way of temporal life contrasted with a way of temporal death. In addition, the lengthy quotation from Isaiah in 2 Nephi 12–24 can be read as a great panorama oscillating between descriptions of life and descriptions of death. In the writings of Isaiah, descriptions of temporal life (health and prosperity) and death (disease and destruction) often serve as metaphors for their spiritual counterparts. However, detailed consideration of these matters goes beyond the scope of this paper. Implications for Interpreting the Book of Mormon The paradigm of a way of life leading to eternal spiritual life diverging from a way of death leading to eternal spiritual death is fundamental to the Book of Mormon. An understanding of this concept aids greatly in interpreting the Book of Mormon. In fact, I believe that a grasp of this model is necessary to comprehend fully the essential message of the book. Despite variations in emphasis and vocabulary, the Book of Mormon prophets held a unified view of spiritual reality. This unified view may be illustrated and confirmed by superimposing the different diagrams used to depict the message of each of the texts earlier in this article. Comparison and correlation between the different texts is facilitated by this maneuver. For example, correlating Alma 5 with 1 Nephi 11–15 (figs. 6 and 9) makes it apparent that the fold of the devil described by Alma is identical, for practical purposes, to the great and abominable church of the devil described by Nephi, as mentioned previously. This connection readily allows one to understand that the church of the devil consists of those who follow the voice of the devil, namely all those not following the voice of Christ. The church of the devil is therefore a metaphor for those walking in the way of death; and the church of Christ, for those walking in the way of life. Such a realization serves as a healthy antidote to misguided attempts to equate the church of the devil with specific historical institutions. This technique of simultaneously considering the different ways in which the different texts address an issue serves to bring the issue into sharper focus. Consider the nature of spiritual death after probation. It is apparent from this type of analysis that hell, captivity to the devil, misery and endless torment, everlasting filthiness and unrighteousness, lake of fire and brimstone, outer darkness, and second death are intimately related ideas. These different ways of describing the final state of the wicked complement one another and enrich our understanding. The same is true of terms and phrases that describe the final state of the righteous after probation: purity and joy, heaven, peace, kingdom of God, presence of God, eternal life, and rest of God. To enter the rest or presence of God is to possess spiritual life. Consider as well the value in seeing the essential identity between Nephi's concept of going through the gate and King Benjamin and Alma's concept of being born of God. This identity is suggested, even required, by the technique of interpretation I am proposing. Grasping the equivalence of being born of God and going through the gate clarifies a critical concept. The spiritual "rebirth" is best understood as the beginning of one's journey in the way of life, rather than its culmination. Only those who have truly been baptized by fire (born of the spirit) have entered into the strait and narrow path that leads to eternal spiritual life. Indeed, it is the very experience of being born again, the mighty change of heart, which wrenches one out of the way of death and into the way of life. Real progress in the way of life begins with being born of God. Therefore, this spiritual birth should not be conceptually deferred to the end of the path. An Accurate Understanding of Hell The Book of Mormon has much to say about hell or the second death. Surprisingly, despite this, it has been my nearly uniform experience that many Mormons are unsure of whether they "should" believe in hell or not, except of course, as the destination of the sons of perdition. Those who accept the idea of hell for other than the sons of perdition almost invariably conceive it in one of two ways. One idea is that hell is equivalent to the spiritual darkness and unhappiness created as a result of our sins, which is experienced during probation (mortality or postmortal spirit world) until we repent.12 The other idea is that hell refers to eternal regrets that those in the telestial and terrestrial kingdoms feel for not having made it "all the way" to the celestial kingdom. Both of these ideas are inaccurate and both trivialize the meaning of hell. Hell is not the same as the first spiritual death, the spiritual darkness of mortality, as severe as this experience may be at times. It is rather the awful state of misery and endless torment, captivity to the devil, and second death that comes upon all those who waste the days of their probation by refusing to repent. This everlasting destruction does not come upon men in the days of their probation. It comes after, when the opportunity to repent and receive mercy is lost. It is this very punishment of the "last day" that is withheld during probation to give us an opportunity to repent. Neither does hell refer to regrets of those in the telestial and terrestrial kingdoms. Such regrets about "not going higher" may or may not be experienced; our canonized scriptures do not address this issue.13 Regardless of whether such regrets actually occur in the eternal worlds, they do not constitute hell as defined in the scriptures. To restate: hell is the state of endless torment, second death, and captivity to the devil experienced by the wicked as required by justice after probation. Inhabitants of the telestial kingdom have been redeemed from captivity to the devil and are, therefore, not in hell in the telestial kingdom (see D&C 76:81–85, 103–6). It is even less appropriate, of course, to speak of terrestrial citizens as being in hell. Apparent Contradictions between the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants Some readers may be disturbed by allusions in this paper to apparent contradictions between the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants. At the risk of increasing this discomfort, but to achieve a clearer exposition, I will now summarize these apparent contradictions as follows: •The Book of Mormon describes only two final outcomes for all mankind, while the Doctrine and Covenants describes four: celestial kingdom, terrestrial kingdom, telestial kingdom, and sons of perdition. Furthermore two of these four, celestial and telestial, are described as having even further subdivisions (see D&C 131:1–2; 76:98). A detailed consideration of the apparent contradictions between the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants cannot be accomplished in this already long article.14 Here, I will confine myself to several brief comments. It is imperative to realize that the Book of Mormon model is not "wrong."15 The Book of Mormon paradigm is simply less detailed or less complete on some issues compared with information in the Doctrine and Covenants. Thus the separation of the righteous, who participate in the first resurrection, into two groups, celestial and terrestrial (see D&C 76:50–80) can be seen as a modification by addition of detail to the Book of Mormon model. The same can be said of the separation of the wicked, who participate in the second resurrection, into two groups, telestial and sons of perdition (see D&C 76:81–107, 28–49). Likewise, the eventual redemption of the majority of the wicked from the second death or hell is a detail omitted from the Book of Mormon, apparently to further the purposes of God (see fig. 10 for the addition of these details).16

Figure 10. Alma 12:31-37; Alma 40:11-14; 2 Nephi

9:11-14 Abinadi's depiction of those who died ignorant of Christ as receiving eternal life (see Mosiah 15:24) is better explained as a reflection of the Book of Mormon paradigm than as a direct contradiction to Doctrine and Covenants 76:72, which portrays the same group as inheriting the terrestrial kingdom. In the Book of Mormon paradigm, mankind is dividing itself into two groups by choosing between the two options of eternal life and everlasting death. All the righteous, including those who sinned ignorantly and are covered by Christ's atonement, eventually receive eternal life in heaven in the presence of God; all the wicked receive everlasting death. From the perspective of the Book of Mormon model, those who die ignorant of Christ must inherit eternal life. From the perspective of modern revelation, Abinadi's statement (and even D&C 76:72) represents an oversimplification of reality. Some of those who die ignorant of Christ do inherit eternal life, as we currently understand the term, and some do not (see D&C 137:7–9; 76:72–80; 138:28–37). By extension, even our current understanding of ultimate spiritual realities must be limited, incomplete, and oversimplified. The problem of the apparent discrepancy between the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants with respect to the duration of the probationary period can also be resolved quite satisfactorily. Again, it is critical to remember that more detail about some matters, including this issue, is currently available to us than is presented in the Book of Mormon.17 Furthermore, even though the Doctrine and Covenants clearly implies the extension of probation into the spirit world to some extent, it confirms the Book of Mormon emphasis on the overwhelming importance of the mortal probation for those who have an opportunity to hear the gospel. For example, those who hear the gospel in mortality but reject it until afterwards (postmortal spirit world) are said to inherit the terrestrial kingdom (see D&C 76:73–78). It should also not be overlooked that nothing in the Doctrine and Covenants directly contradicts the principle, repeatedly taught in the Book of Mormon, that those who live in the midst of the gospel light and persist in serious wickedness in mortality may completely waste the days of their probation and lose the opportunity to repent, dooming themselves to the second death or hell upon leaving mortality. Mormon's description of the Nephites just prior to their final destruction is especially compelling in this regard: "I saw that the day of grace had passed for them, both temporally and spiritually" (Mormon 2:15). The Nephites of Mormon's time had passed beyond the day of grace spiritually, thus losing the opportunity to receive mercy for their sins. The same may well be true for many in our day. The apparent discrepancies between the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants create the possibility for misinterpretation of both books. It is implicit in figure 10 that I consider the Book of Mormon paradigm of diverging ways of life and death to constitute a basic interpretive framework for the Doctrine and Covenants as well. Details of the ways of life and death found only in the Doctrine and Covenants should be viewed as supplementary to the basic Book of Mormon model, rather than subversive of it. The Doctrine and Covenants does not replace or supersede the Book of Mormon; instead, it builds on the understanding of reality given us by the Book of Mormon. Attempts made to understand salvation and damnation without seriously considering the Book of Mormon are certain to be in error. Concluding Comments The Book of Mormon paradigm of diverging ways of life and death during probation, leading to eternal spiritual life or eternal spiritual death after probation, is a valid and true model of spiritual reality. It is simple but profound and beautiful. The Book of Mormon does not contain every detail we now understand about salvation and destruction. It does contain plain and precious details on the way of life and the way of death. It is written to act powerfully on our hearts and minds to induce us to choose the way of everlasting life. No other book teaches so forcefully the idea that every moral choice moves us either closer to spiritual life or closer to spiritual death. No other book teaches so clearly the role of the Savior in bringing about the way of life and enabling us to progress in it. No other book expresses so well the absolute importance of the mortal probation, nor describes as well the nature of the awful state awaiting those who waste the days of probation. A correct understanding of reality in our time is dependent upon the Book of Mormon. Notes 1. Some readers have wondered why I have chosen to discuss the texts in the order listed. I commence with Alma 12:31–37 because I first began to conceive the ideas for this paper while pondering this text in October 1987, and because it succinctly alludes to almost all the concepts I wish to develop. I treat the other texts in the order which they appear in the Book of Mormon, with the exception of the discussion of Lehi's dream. I have chosen to discuss this material last, both because of its complexity and because of its potential to aid in unifying the message of the other texts considered. There are two additional closely related texts that I do not examine in detail. Lehi's discourse (2 Nephi 2) on the principle of opposition in all things is inherently related to the opposing ways of life and death. For an insightful analysis of this text see A. D. Sorenson, "Lehi on God's Law and Opposition in All Things," in The Book of Mormon: Second Nephi, The Doctrinal Structure, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1989), 107–33. Alma 36 is also a classic example of a text's organization around the principle of the way of life versus the way of death, both conceptually and literarily. I will not discuss this text in detail because of its thorough treatment by John W. Welch, "A Masterpiece: Alma 36," in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, 1991), 114–31. I will, however, comment briefly on Alma 36 in the "Discussion" section of this paper. 2. It must be understood that we can perform the labor of individual repentance only with God's help or grace (Alma 13:30; 2 Nephi 10:24). 3. I remind the reader that this summary and the foregoing exposition are applicable only to accountable individuals who hear the word of God. 4. I would also like to suggest the possibility that the divergent dualistic conceptual symmetry I have described and illustrated in this paper may be the intellectual substrate or prerequisite for literary chiasmus. In other words, before chiastic writing there was a revealed fundamental perception of the spiritual universe as a great chiasm of life versus death. Readers unfamiliar with chiasmus should see John W. Welch, "Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon," BYU Studies 10/1 (1969): 69–84; Noel B. Reynolds, "Nephi's Outline," in Book of Mormon Authorship, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1982), 53–75; and John W. Welch, "Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4/2 (1995): 1–14. 5. Bruce W. Jorgensen—correctly in my opinion—considers Lehi's dream to be the key to understanding the typological and literary unity of the Book of Mormon. See "The Dark Way to the Tree: Typological Unity in the Book of Mormon" in Literature of Belief, ed. Neal E. Lambert (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1981), 217–31. 6. James H. Charlesworth, "A Critical Comparison of the Dualism in 1QS 3:13–4:26 and the 'Dualism' Contained in the Gospel of John," in John and the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. James H. Charlesworth (New York, N.Y.: Crossroad, 1990), 76 n. 1. 7. My current opinion is that the Book of Mormon does not definitively address the question of absolute dualism. 8. See Charlesworth, "A Critical Comparison," 76–106; James L. Price, "Light from Qumran upon Some Aspects of Johannine Theology," in John and the Dead Sea Scrolls, 9–37; Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John Vol. 1, 2nd ed. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1979), lxii–iii; and James H. Charlesworth, "Reinterpreting John," Bible Review (Feb. 1993): 19–25, 54. 9. Charlesworth, "Reinterpreting John," 22 and Brown, The Gospel According to John Vol. 1, lxii–iii. 10. I am aware that Bible scholars debate the authorship of the Johannine literature and that no consensus has been reached. However, in my opinion, the conclusion that the apostle John was the author of both the Gospel of John and the book of Revelation is inescapable after considering 1 Nephi 14:18–27; John 21; and Doctrine and Covenants 7. 11. It is my impression, based on admittedly insufficient study, that Joseph Smith in his own preaching and writing made minimal, if any, explicit use of dualism in presenting the gospel. If this impression were correct, it would constitute indirect evidence that Joseph Smith was not the primary author of the Book of Mormon. 12. See Larry E. Dahl, "The Concept of Hell in the Book of Mormon," in Doctrines of the Book of Mormon, ed. Bruce A. Van Orden and Brent L. Top (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, 1992), 42–57. Also see my review of this article in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 5 (1993): 300–304. Larry Dahl's theology of hell differs considerably from mine. I recommend a careful reading of his article as a mechanism for bringing the reader's thinking about hell into sharper focus. 13. Joseph Smith did teach that "the great misery of departed spirits in the world of spirits where they go after death, is to know that they come short of the glory that others enjoy and that they might have enjoyed themselves, and they are their own accusers," Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, 1938), 310–11. This statement has reference only to the postmortal spirit world and not the state after the resurrection. Furthermore, this brief statement was clearly not intended to be a complete theology of hell. 14. I plan to examine some of these issues in a forthcoming paper entitled "The Theology of Hell in the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants." 15. I realize that I also ask the reader's forbearance in accepting, at least temporarily, my Book of Mormon paradigm. 16. See Doctrine and Covenants 19:5–12. God apparently omitted the concept of the redemption of the wicked from hell from the Book of Mormon and the Bible in order to optimize the probability of repentance among his children. 17. The answer to the question of why the concept of preaching the gospel in the spirit world is not taught in the Book of Mormon is debatable. It is quite possible that this doctrine was never revealed to the Nephite prophets. Alternatively, perhaps it was revealed to the Nephite prophets but not to the people in general. It is also possible that vicarious work for the dead and preaching the gospel in the spirit world were generally understood and practiced among the Nephites after Christ's visit to them. If so, Mormon elected not to transmit this information to us. |